By: H.A.P. Smith ©

Approximately written in the early 1900’s

With Thanks to Mr. Ray Stevens who got this article from H.A.P.Smith’s son

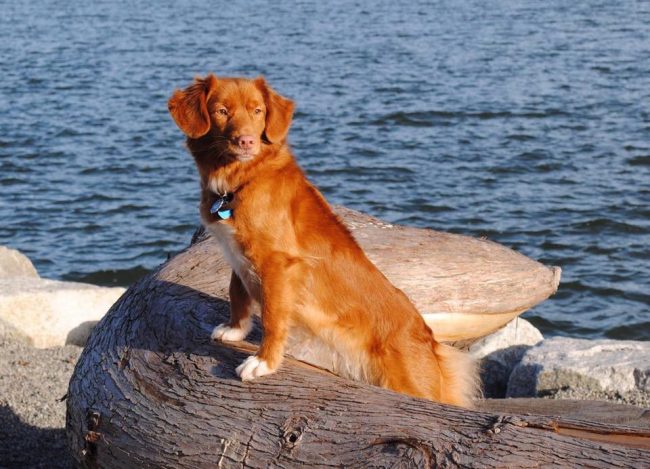

With nose as true as the Pointer, with sight as keen as the Greyhounds with endurance as great as the Foxhounds, with courage equaling the Bulldogs, with disposition as playful as the Spaniels, with coat as dense as the Otter, and with love for his master more fervent than that of any other living thing, and his colour is fox red from the end of his nose to the tip of his busy bushy tail, save a white dash on his broad chest and in some specimens a white blaze on the face. His weight about fifty pounds (bitches 40). His height at the shoulders twenty inches, wide sculled with moderately large pendant ears.

The above is a fair description of the Tolling whose equal as a duck dog the writer has yet to meet. He has the traits of his progenitor the Labrador Retriever, with the added ability to attract or toll his game. The photo of the Labrador Dog in Forest and Stream of the 26th of April could easily be mistaken for a Tolling Dog, but for his colour. So alike in head are they, that at first glance I thought Mr. Sherwood had preceeded me in writing of my favourite the “Toller”. It no doubt will be news to many of the readers of Forest and Stream that the “playing” of the Tolling Dog near the water will attract the wild duck.

In Nova Scotia our best game ducks are the Blue Winged Duck (or Black Duck) and the Blue Bill (or Broad Bill) and both these birds will toll to the antics of the Tolling Dog. The Butter Ball and Meganser ducks will also toll, but the Whistler will jump into the air at the sight of him, as if a gun was discharged into their midst. Sea ducks and fish ducks such as Coot etc. seem to take no notice of the dog, and he has no attraction for them. The idea of this tolling ducks came from the fact that the fox has been known for many years to posses the power to attract wild fowl by reason of his colour and his movements along the shore, and many a fat black duck has paid the penalty of his curiosity and furnished a meal for foxy old raynard on the shores of inland lakes.

It was my privilege and delight to see a fox at work on one occasion. We were moose hunting near the “Boundary Road” in Nova Scotia and as our canoe turned a bend in the Coufang River I saw directly ahead of us and in plain sight four black ducks. Wondering why they did not fly at the sight of us I glanced ahead of them, and there on top of a flat rock which projected into the water, lay a fox with his nose between his paws. Every second or so he would raise his brush and give it a flip from side to side. The ducks were swimming directly toward him intently watching that white tipped tail and not more than fifteen yards away from his waiting hungry jaws. Just then my hunting companion coming down from the river in the canoe behind us and catching sight of the fox shot him. The bullet from his winchester hit the rocks beneath him and spoiled what otherwise would have without a doubt ended in the bitter tragedy, and have been a sight which vary few have ever witnessed. I have always felt perfectly certain that the fox would have carried away with him one of those four birds, a victim of curiosity. But what a transformation that bullet worked. Into, the air went fox, ducks, and pieces of granite boulder, and as my hunting companion recounted as he lowered the rifle between his knees, “I guess that rock was red hot, the way that fox took to the air.”

If you are a dog man, the first time you see a Tolling dog, your attention will be at once arrested. Therefore let us suppose that you meet the writer with a pair of his Tollers at heel, and after looking critically at them, you remark (as hundreds have done before) what kind of dogs are those? Chesapeake Bay’s or what? If time is no object, the answer will probably be they are Tolling dogs, and when the explanation is forth coming, that they are used to toll ducks within range of the gun. Your questions will come thick and fast, such as, do they go in the water? How far will ducks come to the dogs? Do the dogs know they attract the birds? Will they retrieve the birds you shoot? And thousand others. But if time is limited you would likely get the answer, oh they are duck dogs, or just dogs, I guess.

But we will suppose you are a duck shooter, and also skeptical, and come from Missouri and want to be shown, and it is finally agreed that we repair to where we know Black ducks congregate. It is not yet daylight when we reach our blind on the edge of the sandy shore of the bay. This blind is one I have tolled many a fine shot from, and is composed ashore in the surf, and a few old roots of trees, the whole covered with dead sea weed, and just large enough o comfortable as possible, and pulling our coat collars up, and our wool caps well down, for the month is December, and terrible cold, All the lakes are frozen and the ducks are now in their winter feeding grounds.

You turn your head and see the yellow flicker of a lamp through the kitchen window in the farmhouse across the warmth from the big wood stove an hour ago, as our steaming tea, was eaten, and you half wish yourself back there again. It is “Star Colour” not a breath of air, and very frosty. Our dog is curled up tight, his nose covered by his fox-like tail, and he is the only one of the three of us comfortably warm. But just listen to those Black ducks as their trembling quacks reaches us from out they’re in the Bay. Buff hears it too, and quick as lightning his ears prick as he raises his head. If you touch him now you will feel him trembling but not with cold, only supressed excitement, as now the East begins to pale, and presently objects are dimly discernable. Those old stake slats out there stuck up through the sand look like a flock of geese, while in the grey light the bridge spanning the North Cove looms up like a church spire. We hear the swish of wings as ducks fly from the salt creeks where they have spent the night, and as they join there companions in the Bay in front of us, create quite a commotion among them.

Presently we see a black line on the glassy surface of the water, which slowly developes into a flock of twenty birds or more. The tide is almost up to our blind this morning and everything seems to favour us. The ducks are now in the zone of this shore from years of constant persacution. About two hundred yards away they keep their wings and preen their feathers as the rising sun begins to warm them, and now I guess I will “show the dog”.

Reaching into the hand pocket of my hunting coat I pull out a hard rubber ball. Just look at Buff, he has been watching the ball, did you ever see such concentration as he watches that sphere of rubber, next to his master, it is the dearest thing to him on earth. One bounce of it on the kitchen floor will lure him from the finest dish of roast beef scraps and gravy without a moments hesitation. I can devine your thoughts with out much study now, you are thinking “what a shame to scare those ducks” and that perhaps they could come on shore later on as the tide begins to fall, and that you can’t keep feeling certain that every duck will jump as soon as they see the dog.

But wait, you watch the ducks, and what ever you do don’t shoot until I give the word, for it is the sure ruination of a tolling dog to shoot over him while he is outside the blind. If you do so your dog will soon want the first shot himself, and when the birds come close in all probability he’ll plunge in after them, without waiting for the gun.

Smooth patches of sand stretch out upon each side of us and afford perfect footing for the dog, and we can play him upon either side of the blind. I toss the ball and away goes Buff, picking it up he canters back and drops it in my hand, out again goes ball and dog. I watch you face and it is a study as through the peek holes in the seaweed you anxiously watch the birds, and this is what you see. With stretched necks and wondering eyes every duck looks intently at the dog, and as the ball falls in among some dead sea weed causing him to use his nose to find it, his bushy tail works and wiggles above the beach grass and a dozen birds turn and swim for shore, their necks a second ago stretched so long now disappear as they fold them in and with soft meaup-aup-meaup they swim rapidly towards us, with just a gentle air of wind aiding them. Buff plays beautifully, returning with the ball even faster than he scoots after it. How round the birds look with their necks drawn in, giving them a stupid appearance and the sunlight shimmering from the yellow bills of the drakes. And now as the dog comes towards us again the hot scent of black ducks strikes his sensitive nostrils, and stopping with up raised paw he looks towards them, but good old boy, a chirp brings him back to us. Not for words would he refuse to play. See him tremble as we push up the safeties of our guns, and here are the birds right against us, though not well bunched, being strung out across our front. They are only thirty – five yards or so away when Buff drops the ball into my open palm for the last time, and I whisper, down. Now then there are is one of two things to do, we may raise up and shoot, picking out our birds and trying to stop one with each volley, or remain quiet until the ducks begin to get uneasy and not seeing the dog start to swim away, when they will hinvariably bunch. If you can forget the freezing nights and blustery days when you have almost perished waiting for a shot, or perhaps the long crawls through known birds, then let us each try and make a double, and be satisfied. But if you have only occasionally had a flock shot, and would like one now, we will hold our fire, and so we dicide to do. See that old chap stretch his neck and swim up and down looking with the keenest of all eyes for the dog, and now, up go all heads and turning slowly from us the birds swim together with their heads turned sideways looking over their shoulders at the blind. I nod and two pairs of twelve Bore barrels loaded with 3-1/2 drams of dead shot smokeless and 1-1/4 oz. No. two poke out above the fringe of seaweed of the blind. As we raise to shoot Buff peeks over the blind beside me with a whimper and stiffened sinews he awaits the report. Both shots snap out as one and into the air seven terrified birds spring straight up, three of their number falling to our second barrels. There are two cripples, one which swims about in little circles, shot through the head in front of the eyes, another wandering off as fast as his rudders will allow, we each kill our bird. Buff by this time has almost reached the nearest drifting victim, watch him swim! There is only one breed of dog could catch him now and that the Tolling dog. No need to tell him to retrieve, dropping the bird on the sand he plunges in again and again, until the eighth and last duck is safely recovered. Buff takes a roll in the sand and a shake and trotting up to me rubs against my leg, and while he looks up into my face I stroke his wet hair, wet only on the outside, for no water ever penetrates to the skin through that otter coat, and if he and I were alone I would take his honest head between my hands and whisper in his ear “good boy” while with a funny little growl in his throat he would say in his own way “we did the trick.” He always looks for this following a successful toll.

As a surf dog the Toller has no equal and will persevere again when dashed ashore by heavy breakers until he at last stems the undertow. Last winter I feared I had lost Buff upon two occasions. Shooting from this very blind I wing broke a black duck, and giving chase the dog swam after his bird right out to sea beyond my anxious sight. The tide had turned and I ran along shore with frantic haste trying to locate a boat, away along past Red Head there, you see two mules below us, until at last I gave it up and sorrowfully returned to fetch my gun left behind in the blind. My dogs few little imperfections were all forgotten, and every cross word spoken to him was regretted. But to my utter surprise and joy upon reaching the blind, there lay the game little dog with the duck beside him. The distance he swam by conservative estimation, through the ice cold water, must have exceeded three miles, and he seemed none the worst for it.

Upon the other occasion while flight shooting by moonlight up the wide creek you see beyond the bridge there, a winged tipped duck fell among the floating, grinding ice cakes tide. Away went Buff right into the worst of it and both dog and bird disappearing beneath that floe. It seemed ages until his head at last appeared in the moon blaze with the bird softly held between his jaws.

And now let me tell you that ducks will not toll to windward. They will come to the dog across wind, or as you have just seen from the windward and also when there is no wind. Black ducks toll with their heads drawn down, Bluebills with heads up and necks struck out. Butterballs on their tails almost, and all the Megansers with heads erect and necks straight up.

Perhaps the Tolling dog is most deadly when shooting ducks before they leave the lakes in the fall, and when the birds are young. I have seen young Black ducks swim so near the blind that their pads could be distinctly seen beneath the water.

Bluebills are said to be the easiest of all birds to toll, but although I have had many fine shots at them, in this manner my personal experience teaches me that the black duck tolls the best, and I have seen wary birds in the month of January act like perfect fools at the sight of a well played dog. They seem to be hypnotised and when once their gaze has become centered upon the dog they will scarcely notice moving objects.

It is as natural for a Tolling dog to retrieve and play with a stick or other object thrown as it is for a setter to point or a coach dog to follow a team. Most duck shooters use sticks to toll their dogs with, and some a lot of sticks, but a properly trained dog needs but one object to work upon. If space permitted I should like to give my method of training these dogs, but I must forbear.

The history of the Tolling dog from all I can gather is as follows. In the late sixtiesª James Allen of Yarmouth, Nova Scotia received from the captain of a corn laden schooner a female flat coated English Retriever, colour dark red, weight about forty pounds. Mr. Allen had her bred with a Labrador dog which was a fine retriever, the first litter of pups made very large dogs, even larger than their parents, and were splendid duck dogs. Several of these bitches were bred to a brown cocker spaniel imported into this province from the U.S.. These dogs were bred throughout Yarmouth County, particularly at Little River and Comeau’s Hill and a majority of them are a reddish brown colour. Later on a cross of the Irish Setter was introduced. Occasionally a black pup appears and of course makes just as good a retriever and water dog as his red brothers, but is not so valuable because he can not be used as a Toller.

Only this year distemper in its most violent type destroyed a number of these dogs, including valuable bitches together with their young litters. I am fortunate as to own a dog and two bitches and shall try to perpetuate the breed. This grand dog should be carefully bred and given a class at the dog shows, for he certainly is on account of his tolling ability in a class all his own.

H.A.P. Smith

© Please note that this is a translation from the author and any spelling or grammatical errors are typed in as he has written.

* That would be the 1860’s.